Professional photographers swear by the "golden hour" as the time of day with the best lighting. Discover what it is and how to take advantage of it.

If there's one thing that can make or break a photograph more than any other, it's lighting. You might have the most incredible landscape or stunning portrait model, but without the right quality of light you can still be left with a flat, dull, and uninspiring photo.

This is particularly true in outdoor photography - it can often be difficult or impossible to use artificial lighting to illuminate your subject, so you're completely reliant on the natural light.

As a result, it's critical to find the right time of day to shoot your outdoor scene. Thankfully, professional and amateur photographers have been thinking about this problem since the invention of the first camera, and have found the perfect solution - the so-called "golden hour".

What is the Golden Hour?

The golden hour, sometimes called the "magic hour", is roughly the first hour of light after sunrise, and the last hour of light before sunset, although the exact duration varies between seasons. During these times the sun is low in the sky, producing a soft, diffused light which is much more flattering than the harsh midday sun that so many of us are used to shooting in.

Lighting during the golden hour is soft, diffused, and warm. Image by Martin Sojka.

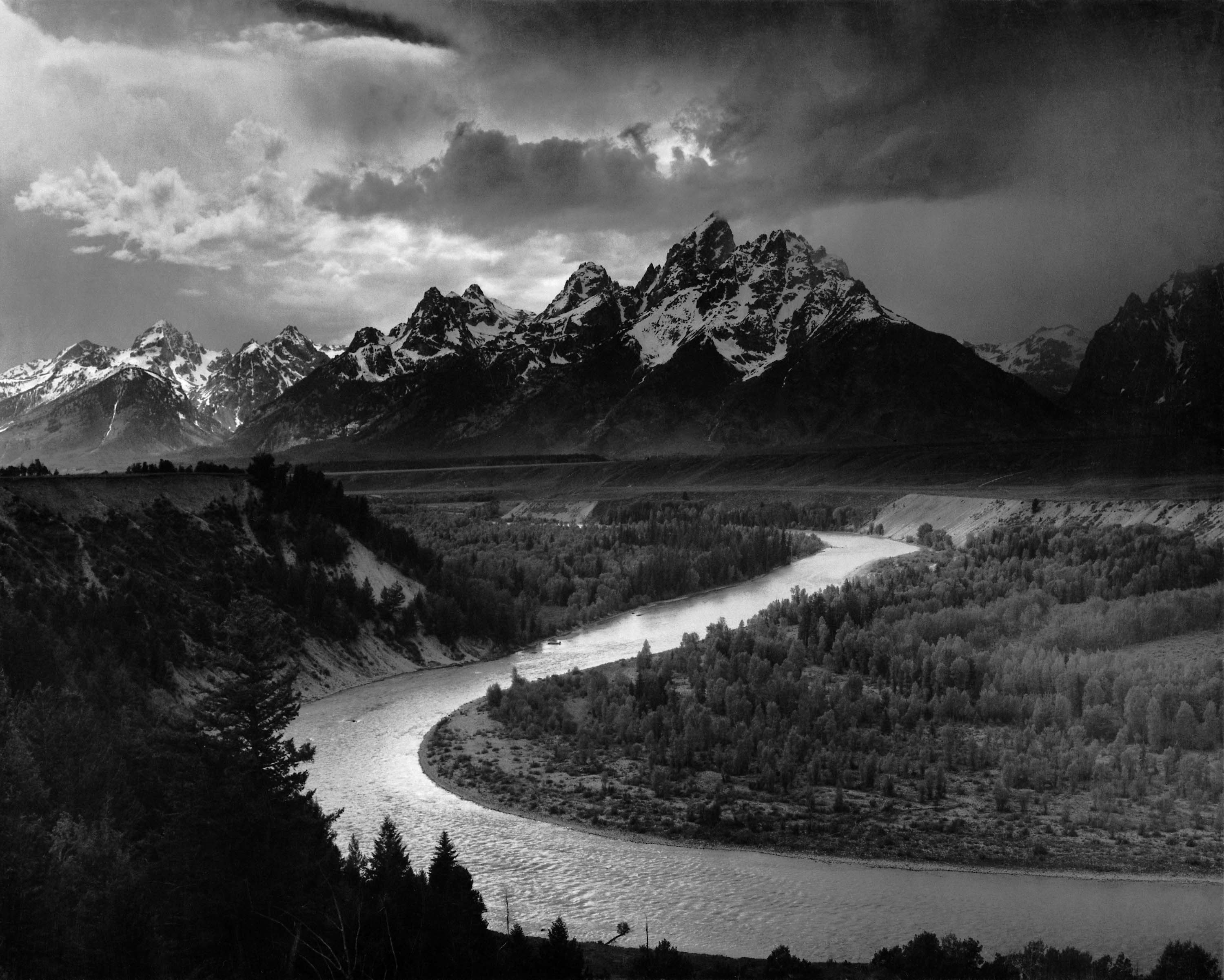

by Mark Hamblin

The light of dawn is special. At first it’s a cool blue as darkness retreats to reveal a new day. Then, oddly, as sunrise is imminent, the light is flat and almost colourless.

But just as the sun breaks the horizon the landscape is bathed in the most wonderful light, illuminating everything it strikes in hues of red and orange. For this brief period of the day the landscape is a magical place – full of atmosphere and a real tonic for those who witness it.

It is these transient moments of light, this explosion of colour and this unfolding drama that makes dawn an event not to be missed.

There’s no doubt that great dawn light will make your images extra special, but are you prepared to head out in the gloom in the hope of capturing that magic?

It’s a risk. It might be cloudy. You might get cold. You might be tired. You might not get there in time.

There are lots of reasons not to go, not to get out of bed at 3am, not to walk for an hour in the dark. But the reality is that to get the images you crave, you have to. You have to push yourself. You have to make the effort.

Shooting golden hour photography in the dawn hours is more of a physiological challenge than a photographic one. It helps a lot if you team up with someone, as you are almost certain to make the effort if you have arranged to meet a friend. You must also plan well and be prepared.

This is key because you need to be clear where you are heading, how long it’s going to take you to get there, and be confident that you can find the right spot.

A pre-visit in good light is the best way to determine this, and is useful for scouting the location for suitable viewpoints. Take a GPS with you, if you have one, to mark favoured spots.

Some landscape views may only work well at certain times of the year, depending on the position of the sun. You can determine where this will be by using a sun compass or an app that shows you where the sun will rise each day.

From this you can then work out exactly where you need to aim your camera, and also which parts of the landscape are going to be illuminated in golden light.

When shooting at dawn before the sun is up, the best colour is usually in the eastern sky. Try to find a focal point to set against this.

Perhaps a silhouette of a tree or building. Alternatively use calm water to reflect the sunrise. A reed fringed lake or one surrounded by trees works well. As the colours intensify, keep shooting as the light changes, and reframe your shots to capture a range of images.

To shoot the sun as it breaks the horizon, set the aperture to f/16 to get the optimum sunburst effect. It also helps if you partially hide the sun behind a tree or rock to reduce the intensity of light and overcome problems with flare.

Once the sun gets too bright to usefully work with, turn around and shoot in the opposite direction to catch the warm light on the landscape. Any surface that is angled towards the sun will catch the light.

This contrasts really well with any shadow areas, and gives the landscape depth. Choose your position carefully though to avoid your own shadow creeping into the picture!

Shooting at sunrise involves some tricky lighting conditions. Generally, if you expose for the bright sky, the foreground will come out much too dark and lack detail.

The easiest way to resolve this is to use a neutral density graduated filter (for instance an 0.9ND grad) to reduce the exposure for the sky while keeping the exposure for the foreground the same.

Before fitting the filter, take a meter reading from the foreground (excluding the sky) and set this exposure in Manual mode.

Then recompose and fit the filter so that the darker part covers the sky and take the shot.

Alternatively, take one shot with the exposure set for the foreground and a second exposed for the sky, then blend the two images in Photoshop.

Three ways to give your golden hour photography an advantage

Be the early bird

Aim to reach your destination in good time. The best colour in the sky is often 15- 30 minutes before sunrise, so you need to be set up and ready to shoot to capture the quickly changing light.

Ensure sharp shots

Dawn photography means shooting in low light, so take steps to make sure your images are pin sharp. Set up a tripod on a solid base, or push the legs into soft ground to add stability. Use a remote release in combination with mirror-lock up to prevent internal camera vibrations.

Control the exposure

The lighting can be variable at dawn, causing major differences between the exposure for the sky and land. Using Manual metering take a reading from a mid-tone in the foreground and then fit a neutral density graduated filter to reduce the exposure for the sky to balance the shot.

Tips to remember when shooting golden hour photography

Stay dry

Keep an eye on the weather forecast and look out for high pressure with cold clear nights and little or no wind. Mist often appears over rivers, lakes and damp ground, so it’s always worth visiting such locations to increase your chances of successful shots.

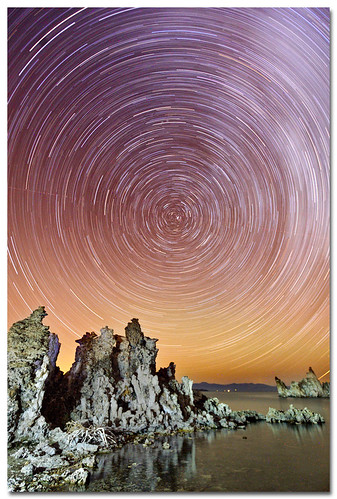

Shoot long exposures

Don’t restrict yourself to low level shooting. If you’re visiting hilly locations, the valleys will be cast in deep shadow until well after the sun is up – so head for the hilltops instead to catch the first rays of sunrise.

References: